Author | Britt Young

Source | https://spectrum.ieee.org/bionic-hand-design

Compile | Lilyann

Editor|Jing Yu

In 1865, science fiction master Jules Verne described how a group of disabled veterans of the Civil War “overcame” their disabilities and created a The story of a rocket ship.

Art comes from life. In the process of writing, Verne learned that more than 60,000 amputations took place during the American Civil War. Thanks to government funding and related patents filed by high-tech companies, the Civil War opened the “era of modern prosthetic technology” in the United States. .

If the two world wars cemented the for-profit prosthetic industry in Europe and the US, nearly two decades of the war on terror have rapidly grown it into a $6 billion industry worldwide.

However, the real market for the prosthetic industry is actually civilian use.

By comparison, about 1,500 American soldiers and 300 British soldiers lost limbs in Iraq and Afghanistan, but in the United States alone, 180,000 people are amputated each year, and more than 2 million people are disabled across the country.

Even more unfortunate is that every year, 1,500 to 4,500 children are born with a physical disability, including Britt Young, the original author of this report.

Original author Britt Young with her Ottobock iLimb bionic arm|GABRIELA HASBUN IEEE

Nowadays, people who design prosthetics are often able-bodied engineers rather than disabled people. These products carry designers’ dreams of high technology and excellent simulation power. This pursuit of technology even makes them ignore the real purpose of prosthetics. – First of all, we must meet the needs of users.

“I’ve tried many of the most advanced prosthetic devices on the market, and because of a congenital condition, I was one of the first babies in the U.S. to have a ‘myoelectric prosthetic hand,'” wrote Britt Young.

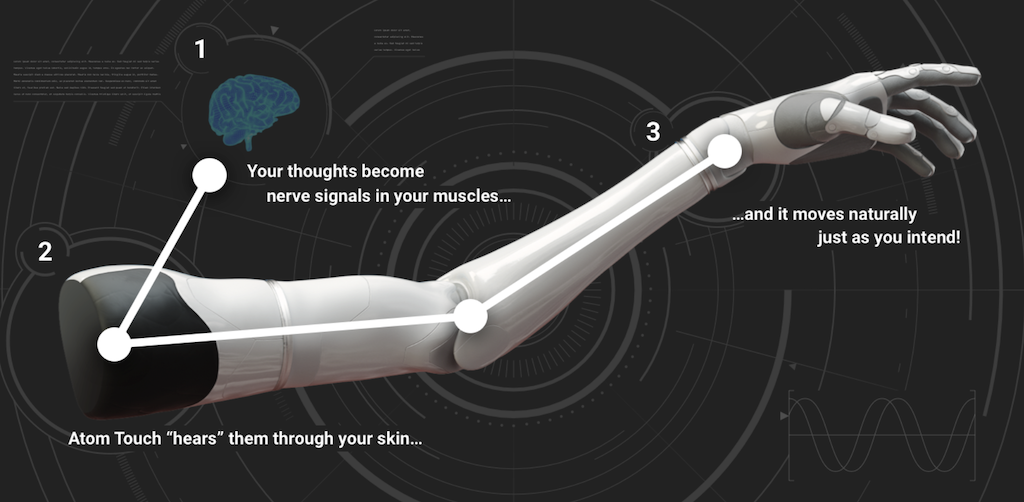

The “myoelectric prosthetic hand” is an electronic device controlled by the wearer’s muscles that relaxes or tightens through sensors in the prosthetic socket.

There are also various “prosthetic hands” on the market, all of which have the common feature that they are striving to achieve the perfect simulation of the human hand: either at the expense of aesthetics, or at the expense of function.

Developers seem to be caught in an arms race of the “bionic hand”: in just over a dozen years, it has evolved from a claw-like structure to a multi-grip precision human hand replica, the most expensive even reaching tens of thousands of dollars.

Likewise, prosthetic limbs are becoming increasingly expensive to develop and even seen as a risky move.

“From the invention of electricity to space travel, every innovation starts with enough madness, and Atom Limbs is no exception,” Tyler Hayes, CEO of prosthetics startup Atom Limbs, said in a fundraising video. He eventually raised from investors to $7.2 million.

Yet after the drastic innovation, has the industry really progressed? We need to go back to the original question: what is the real need for prosthetics for people with disabilities?

The “simulation trap” of prosthetic limbs

In recent years, research on bionic hands has focused on how to develop different gripping methods, which has made the price of products in the market soar.

However, these seemingly amazing bionic technologies, which can help people with disabilities to squeeze the grip, put their thumb on the index finger, or hand the credit card to the opposite person in an elegant way, cannot help people to complete some daily tasks. Routine tasks such as closing doors.

“As cool as the bionic device is, it’s clearly not better than doing things the way I do, sometimes with the help of my legs and feet,” says Britt Young.

In fact, when Britt first got a chance to talk to Ad Spiers, a machine learning scholar at Imperial College London, it was late at night, but he was still very excited about the bionic hand.

As a current research focus, Spiers said, “ From today’s prosthetic reality to sci-fi/anime fantasy, anthropomorphic robotic hands are inevitable. “

In Spiers’ view, prosthetics developers are too focused on form rather than function itself . “The machine intelligence departments at the universities I visited all had at least one kind of artificial robot in development. That’s what the future looks like, but we’ll always find a better way.”

To understand how people with disabilities use their devices, Spiers started a study using cameras worn on the subjects’ heads to record the daily activities of eight patients with unilateral amputations, or congenital limb differences.

The findings, published last year in IEEE, include how several bionic hand and body dynamics systems use motions of the shoulder, chest and upper arm transmitted through cables to operate a mechanical mechanical gripper at the end of a prosthetic limb.

In the video, it can be seen that even experienced “veterans” will make clumsy and misoperations when applying artificial hands.

Myoelectric simulation arm developed by Atom Limbs|Atom Limbs

In fact, this study shows that only 19% of the subjects used a prosthetic device throughout the filming, and in this case, the role of the prosthesis is more to support the object on the body, so as to free up another normal limb. Hand handle.

People using non-motorized grippers or simple devices performed tasks significantly faster and more fluidly than more complex prosthetic devices.

Spiers and his team found that there was little difference in use between the EMG single-grip device and the more advanced EMG multi-joint multi-grip electric hand—except that people tended to avoid using the latter to suspend objects, it seems for fear of breaking them.

“We could sense that people who had more expensive multi-grip myoelectric hands were skeptical of them,” Spier said. And that’s not surprising, since most of them cost more than $20,000, were difficult to cover with insurance , and required Frequent professional support to change grip modes and other settings, the entire repair process is expensive and time-consuming.

While some startups are experimenting with new ways of commercializing—“subscription models”—that allow consumers to sustainably perform paid repairs… and ideally, these processes should all be easier and more flexible.

Although research has concluded that “complexity is not the same as effective use”, Spiers believes that most prosthetic research and development institutions today are still focused on modifying the grasping patterns of expensive high-tech bionic hands .

“Anything that’s not next to a grip is thrown away,” he said.

The evolution of the “hand”

If we’re convinced that it’s our hands that make us human, and that what makes the hand even more unique is its ability to grasp, then the grandest blueprint for the prosthetics industry actually rests on our wrists.

However, the pursuit of a more extreme grip is not always the eternal pursuit of the real world. In fact, history shows that people are not always focused on recreating their hands perfectly.

The concept of the hand has evolved over the centuries, “the hand is the tool for manipulating tools.” Aristotle also described in “Soul”, he believes that “man is deliberately endowed with agile hands, because only We have intelligent brains that can use it flexibly.”

The hand is not just an instrument, but a tool to understand or “grasp” the world , not just literally.

Over 1,000 years later, Aristotle’s ideas resonated with Renaissance artists and thinkers.

Leonardo da Vinci proposed on this basis that the hand is the medium that keeps the brain connected to the world . He went to great lengths to study its main components in the anatomy and illustrations of the human hand, which led to more interest in human anatomy.

Fast forward to the mid-18th century, and with the advent of the global industrial revolution, a more “mechanized” worldview began to emerge, blurring the lines between living things and machines.

In her 2003 article, “Events in the Eighteenth Century,” Stanford University history professor Jessica Riskin wrote, “The 1730s and 1990s were an era of The gap between living things and man-made things.”

The design of prosthetics changed significantly during this period: 16th century mechanical prostheses were made of iron and springs and were very heavy, while 18th century body powered prostheses used a pulley system to bend artificial limbs made of lightweight copper hand.

By the late 18th century, metal was gradually being replaced by leather, parchment and cork—softer materials that were closer to everyday life.

The techno-optimism of the early 20th century brought another change in prosthetic design, says Wolf Schweitzer, a forensic pathologist at the Zurich Institute of Forensic Medicine and an amputee.

The Hosmer Hook (pictured left) was originally designed in 1920 as a human-powered terminal device that is still in use today. When driving nails into wood, a hammer tool (pictured right) is often more effective than a grasping tool | Getty Images

He has tried various prosthetic devices and has extensive experience in using them. In his view, entering the 21st century, the design of disabled devices is moving in a more correct direction. “For example, the 21st century body powered open hook is more modern because its design breaks the traditional construction model of the human hand. “

“This kind of bodily powered artificial arm can still see the relationship between man and machine in the industrial society of the 1920s,” Schweitzer wrote on his blog. intensive labor.”

In the original body powered open hook design of the 20th century, one of the devices inside the hook was used to tie a person’s shoes, and the other was used to hold a cigarette. Ad Spiers says the designs are “very functional, with each feature serving a specific purpose.”

According to Schweitzer, as the need for intensive manual labor diminishes in the contemporary era, functional but less-than-realistic devices are gradually being replaced by more expensive but more realistic-looking prosthetics under the new high-tech vision.

In 2006, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency launched the Prosthetics Innovation Program, a study aimed at developing the next generation of highly realistic prosthetic arms.

In the $100 million program, researchers produced two types of multi-joint prosthetics (one for research and one for the consumer market, priced at more than $50,000).

More importantly, this project has also affected the development of similar products, making “more simulation” the first priority of innovation. At this level, today’s multi-handed bionic hand reflects a monopoly of industry concepts .

Prosthetic technology company TRS makes a variety of body-powered prosthetic devices for people’s different sports preferences. Each device is dedicated to a specific task and can be easily disassembled for various activities | TRS

Prosthetic limbs require more “heart” than “skill”

There are still some prosthetic product developers who are pursuing a different vision.

Boulder, Colorado-based TRS is one of the few manufacturers of sports-specific prosthetic accessories, which are generally more durable and cost-effective. The products are mostly made of plastic and silicone accessories, such as soft mushroom-shaped devices for push-ups, ratchet clamps for weight lifting, and concave fins for swimming.

This low-tech sports prosthesis provides surprisingly good user feedback at a fraction of the cost of a simulated bionic hand. While they don’t look like human hands at all, they function even better.

Sophisticated bionic hands try to return the disabled to “wholeness”, allowing them to return to a world where they can “master” with their hands. But in comparison, it’s more important “ to be able to live the lives we want and get the tools we need, not make us look like everyone else. “

The prosthesis produced by Arm Dynamics, with accessories from Texas Assistive Devices, allows disabled people to perform weight training, and the prosthesis itself is inexpensive | GABRIELA HASBUN IEEE

Although many people use bionic hands to re-interact with the world and express themselves, for hundreds of years, in pursuit of more simulation, the industry’s attention has rarely focused on our real needs in our daily lives. ” said Britt Young, the original author of the report.

For most of these years, prosthetic technology has developed rapidly. But if the different roles in this industry (such as medical workers, insurance companies, engineers, designers, scientific researchers, etc.) are always revolving around the same single goal day in and day out, it is almost impossible for them to produce real Something revolutionary.

As a result, has this technological upgrade, which was compared with the “moon landing race” at the beginning, has evolved into a task that has forgotten its original mission – helping the disabled to obtain truly practical tools.

Today, there are some cost-effective, light and portable products on the market that are not technically difficult. Do they need more attention or even consideration for investment? After all, only stable and sustainable cash flow can continue to develop and optimize functions.

Perhaps the core point of what we have learned from this is that only by withdrawing from the scientific and technological competition chasing high simulation can we open up more, more practical, more affordable, and more in line with the wishes of the disabled people. Prosthetic design possibilities.

This article is reproduced from: https://www.geekpark.net/news/307029

This site is for inclusion only, and the copyright belongs to the original author.