The whip of inflation is not over yet, and the whip of interest rate hikes is coming. Higher interest rates will depress consumption through three transmission channels, including borrowing costs, wealth and income.

Oil prices took a brief break ahead of the Memorial Day long weekend, but the national average oil price hit an all-time high again in the first week of June with the arrival of the summer travel demand season.

Consumers are exhausted from 40-year highs of inflation.

The whip of inflation is not over yet, and the whip of interest rate hikes is likely to come again soon.

What is the impact of rapid interest rate hikes on consumption?

Under the attack of inflation before and then with interest rate hikes, can U.S. consumption still top?

Consumer confidence is declining, is consumption really so strong?

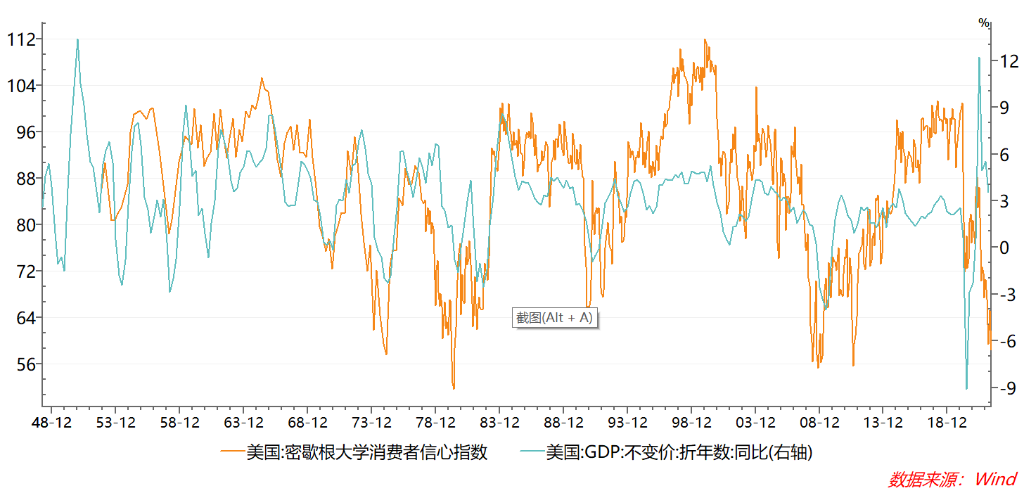

In the past 60 years, private consumption has gradually accounted for 70% of US GDP. Annual changes in private consumption and GDP are highly correlated. There has never been a fall in private consumption but a rise in GDP. Given the outsized role of private consumption in the economy, a dip in consumer confidence below 80 gives a six-month to one-year lead to a recession.

And recently weighed down by inflation, Michigan consumer confidence has fallen below the readings of the 1991 and 2001 recessions, second only to the great stagflation of the 1970s and the 2008 financial crisis.

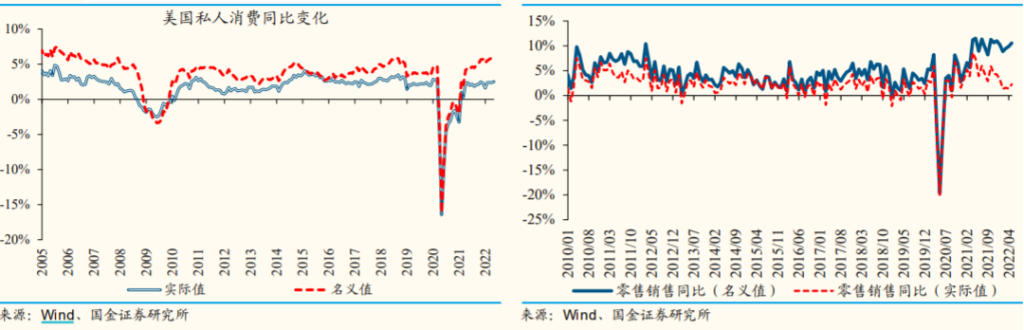

In terms of nominal consumer spending and retail sales, the data remains very strong. The compound growth rate of private consumption in the United States rose to 6% in April, far exceeding the 3.9% average for the past 10 years. At the same time, the compound growth rate of retail sales rose to 10.6%, which was also much higher than the average level of the past 10 years.

But if prices are deducted, the actual level of U.S. consumption is far less robust.

According to the research of Sinolink Securities, after excluding price factors, the compound growth rate of actual consumption in the United States in April was 2.5%, slightly higher than the average level of 2.2% in the 10 years before the epidemic. The actual year-on-year growth rate of retail sales was only 2.3%, which was also slightly higher than the average level of the 10 years before the epidemic.

In the booming consumption of durable goods, contrary to the nominal growth rate, the actual compound growth rate of retail sales of major durable goods such as home appliances, furniture, automobiles, and building materials has dropped sharply, at 30%, 28%, and 8% of the historical percentile, respectively. %, 5%.

The actual service consumption is even weaker, and the actual compound growth rate is only 0.9%. In particular, the compounded year-on-year consumption of non-essential services such as transportation and entertainment, which are repeatedly restricted by the epidemic, is still in the negative range.

So, having established that consumer sentiment and real consumption are falling, the question is, how are inflation and interest rate hikes affecting consumers’ purchasing power?

Inflation squeezes consumption

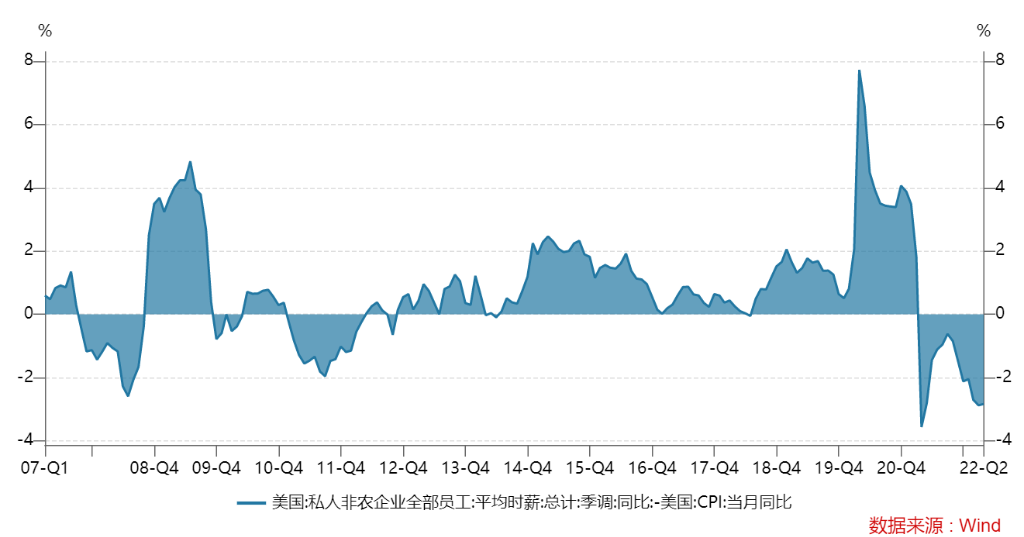

First, the most direct impact of inflation on purchasing power is a decline in real income.

Inflation does not necessarily reduce purchasing power if consumers’ incomes keep up with or exceed inflation. But the truth is that real incomes (adjusted for inflation) have been down for more than a year. That is, while nominal wages are increasing, their purchasing power is decreasing.

With inflation remaining at 8% and wages rising by about 5%, consumers are effectively taking a pay cut, whether they realize it or not. The lower and middle classes, in particular, are worse off, not only because their marginal propensity to consume is higher, but the prices of food, energy and rent, on which most of their income is spent, are rising faster than the overall rate of inflation.

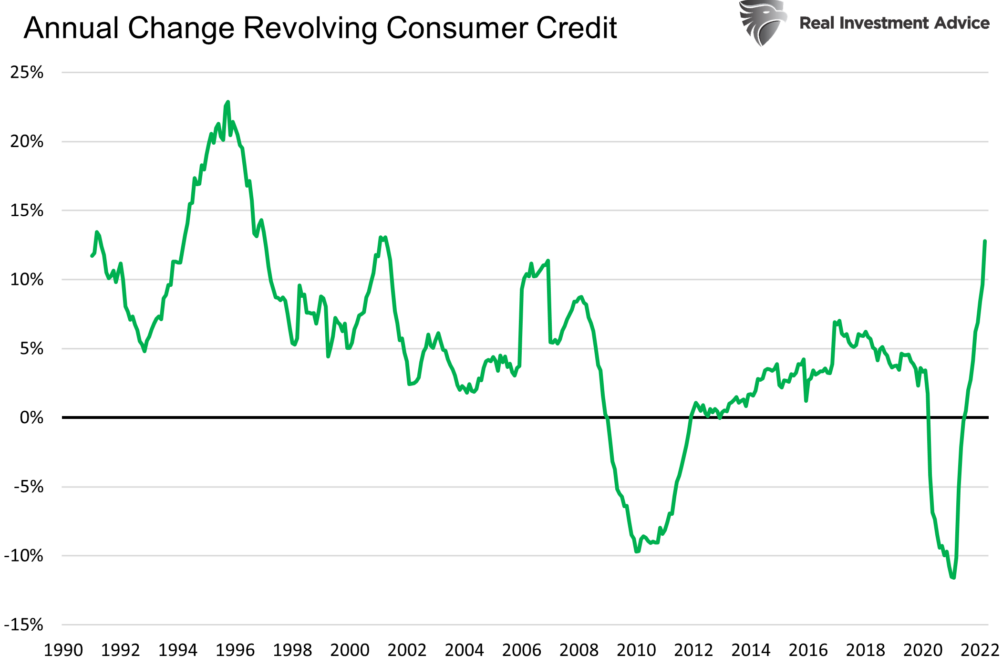

Second, inflation will consume savings and increase debt to dampen future consumption.

In order to maintain a certain purchasing power, consumers will use their savings. Although the absolute value of personal savings is still high, the level of savings adjusted for inflation has actually fallen to an eight-year low. Depleting savings to support consumption also means lower spending or higher debt in the future.

Likewise, consumers have increased their use of revolving consumer credit instruments such as credit cards. Year-over-year growth in consumer credit card debt has climbed to the highest level in more than a decade. Consumers can continue to borrow, but higher credit card rates and larger debt balances will limit future use by consumers, thereby depressing future levels of consumer spending.

The whip of rate hikes is coming

In the face of 40 years of high inflation, the Fed will eventually have to raise interest rates quickly to calm prices even as consumers are exhausted. But is keeping prices down (at least steady) good news for consumption? Not really.

Tight monetary policy will depress consumption through three transmission channels including borrowing costs, wealth and income. Likewise, austerity will also lead to a rise in income and consumption inequalities, masking the dramatic impact on low- and middle-income groups.

A. The cost of borrowing – When the Fed raises interest rates, the cost of new borrowing increases, dampening demand for interest-rate-sensitive sectors of the economy, namely durable goods and housing. The average cost of taking on existing debt is also rising, but lower-income households are more exposed to interest rate risk because of easier access to credit cards and conversion to variable-rate debt.

One of the main channels through which monetary tightening affects consumption in the short term is the cost of borrowing at floating rates. Rate hikes are immediately passed on to the rates banks charge on revolving consumer credit, mostly credit cards. As a result, households that are more reliant on revolving credit (credit cards, etc.) will experience a noticeable increase in costs, reducing their spending on interest-sensitive items. The categories of spending that consumers finance with revolving credit mainly include “high-priced” durable goods such as household goods and electrical appliances. The consumption of these items is therefore very sensitive to interest rates. The Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Report for May showed a decline in purchase intentions for homes, cars and major appliances.

And when it comes to outstanding debt, (primarily mortgages at 70%), the impact on consumption is smaller as it is relatively insensitive to changes in the federal funds rate these days. Because more than 99% of outstanding institutional MBS and the majority of household debt (90%) are currently held at relatively fixed rates.

Before the housing bubble burst in 2007, the proportion of outstanding institutional MBS held at an adjustable rate peaked at 12%, and today it is less than 1%. This led to the global financial crisis as mortgage debt became more vulnerable to interest rate risk. This shows that current consumers have reduced their exposure to interest rate risk.

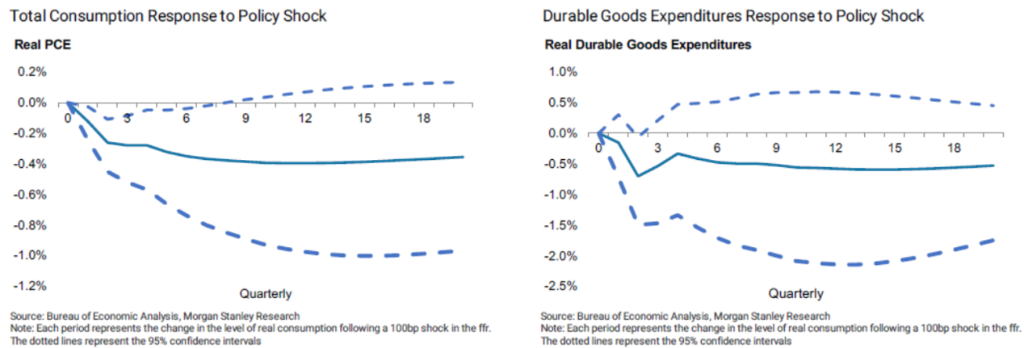

According to the consumption response model constructed by Morgan Stanley, a one-time rate hike of 1% will result in a net decline of 0.3% in real PCE levels in one year and 0.4% in two years. Much of the decline was reflected in spending on durable goods. Durable goods spending fell 0.7% in the two years following the policy shock and 0.5% in the five years. But the response in services and nondurable goods was much smaller. The decline in durable goods was 2.7 times that of non-durable goods and 7.8 times that of services.

At the same time, Morgan Stanley cites research by Johnson and Li (Federal Reserve, 2007) and Baker (2014) to point out that the cost of monetary tightening through credit channels is unequally distributed. Low-income households are likely to take a bigger hit to their spending when faced with an income shock, as they must maintain a larger share of consumption and leverage.

B. Wealth effect – Rising interest rates affect the valuation of financial and non-financial assets, which in turn affects consumption through the wealth channel. Higher interest rates should directly reduce financial wealth through falling bond prices and other asset prices. In non-financial wealth, higher interest rates increase the cost of buying a home, which can hurt home values.

The Morgan Stanley model shows that since 70% of financial assets are concentrated on the balance sheet of the top 20% of households, and the wealth of high-income earners is affected by interest rate hikes, the transmission of consumption to consumption is negligible. Therefore, wealth channels are in The overall reaction after the rate hike was smaller. But it has a more pronounced effect on the bottom 60% of the income distribution.

Rather, non-financial wealth (housing) is more responsive to policy shocks than financial wealth. Compared with financial wealth, non-financial wealth is held more evenly across the income distribution, so the pass-through to consumption through the non-financial wealth effect may be larger than the financial wealth effect.

Taking home buying as an example, Morgan Stanley said real estate assets began to decline more significantly in the fourth quarter following the policy shock. That said, rate hikes have a lagged impact on home transaction volumes and home values.

Higher interest rates will dampen new mortgage originations and, in turn, home sales. But rapidly rising mortgage rates were often accompanied by higher existing home sales in the months after the rate hikes began, as potential buyers saw their last chance to lock in low rates. Home sales activity didn’t peak until about six months after interest rates rose sharply, then trended lower. This has been reflected in May’s increase in U.S. home listings for the first time in 19 years and a drop in total mortgage applications to a 22-year low.

Due to the steeper decline in wealth for the bottom 60%, as well as their higher marginal propensity to consume (MPC). The model shows that five years after a 100 basis point rate hike shock, the implied impact of consumption by the bottom 20% is a 0.26% drop in real personal consumption expenditures, while that of the top 20% is only down 0.04%. Consumption by low-income households through wealth channels has been hit harder.

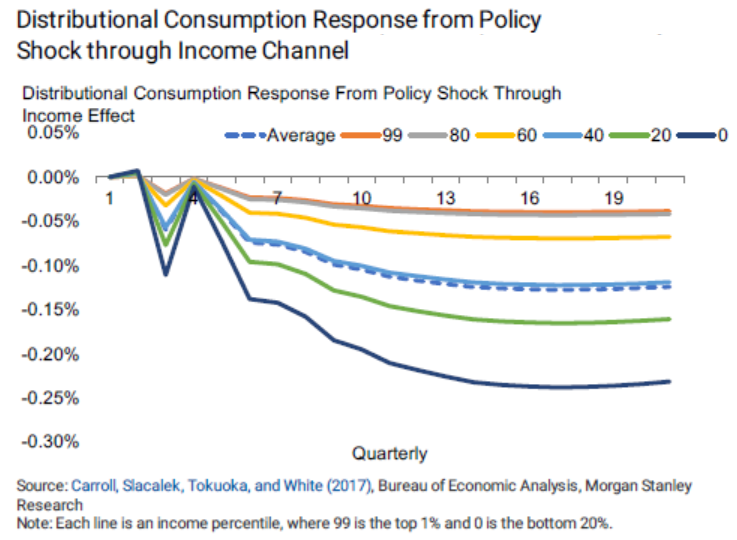

C. Income effect – High interest rates slow the economy, reducing the demand for labor, which in turn reduces labor income. The reduction in labor income will ultimately reduce consumption. Morgan Stanley also noted that the declines in income and consumption have not been consistent, with households also at the bottom of the income distribution showing a stronger consumption response.

Monetary tightening causes a drop in disposable income, but its effect is delayed and smaller than the immediate drop in consumption caused by changes in borrowing costs. The modelling shows that the decline in income five quarters after the tightening shock will have a more meaningful impact on consumption. Real disposable income fell 0.1% in the first year and 0.3% in the two years, while consumption fell 0.3% and 0.4%, respectively. Consumption fell more than income.

Similarly, in the income effect, monetary tightening will have a greater impact on households at the bottom of the income distribution. Reasons aside from the largest decline in disposable income; a low savings buffer; and a larger fall in government transfers following a contractionary monetary shock.

The model shows that three years after the shock of a 100 basis point rate hike, the impact of consumption by the under 20% is a 0.24% drop in real personal consumption expenditures, while the real personal consumption expenditures of the top 20% are only down 0.04%.

The strong consumption of durable goods may be coming to an end, and whether service consumption can be significantly boosted in the future will become the key to testing the quality of US consumption. Slowing inflation and tightening into a fast-track rate hike are gradually putting consumers in a bind.

A drop in consumer confidence does not mean that the economy is bound to decline, but after all, 70% of the economy is closely related to the fate of consumers.

edit/irisz

This article is reprinted from: https://news.futunn.com/post/16344718?src=3&report_type=market&report_id=207901&futusource=news_headline_list

This site is for inclusion only, and the copyright belongs to the original author.