Original link: https://sehseh.substack.com/p/65e

?The full text is easy to read and share version| She weaves a network of cultural care in her hometown to pick up the aboriginal people who have been left behind by the medical system

Editor’s note:

Today (August 1) is Indigenous Peoples Day in Taiwan. For decades, there has been a gap that cannot be ignored between the average life expectancy of indigenous peoples and the general population: according to a survey by the Ministry of the Interior, in 2020, the average life expectancy of Taiwan’s aborigines is 7.3 years less than the average life expectancy of the Taiwanese as a whole. In 2019, the infant mortality rate among Indigenous peoples was twice the national rate.

At this moment, the “Aboriginal Health Law” is still lying in the Legislative Yuan. The law is related to the issue of ethnic health equality, including details such as funding, cultivating culturally sensitive medical personnel, and building a health database, which need urgent attention. However, in recent years, “tribal cultural health stations” have gradually become popular, allowing culturally sensitive ethnic groups to “take care of their own people”, and have also initially improved the health inequality between ethnic groups.

On Indigenous Peoples Day, the world wants to join readers to meet a woman behind the “Aboriginal Health Law” and Cultural Health Station, who has been working for aboriginal medical care for many years.

Text / Xiao Zihan

Yi Mao. Yi-Maun Subeq is a Taroko, a medical worker, and an important promoter of the Cultural Health Station and the Aboriginal Health Law.

In an era when few people studied aboriginal health, she went all the way from the Institute of Aboriginal Health to the Institute of Medical Sciences, became the first doctor of medical philosophy of the Taroko people, and then actively participated in the reform of aboriginal medical policy. For Yu Yimao, these nearly 20 years of hard work are all to solve the doubts that cannot be answered clinically.

“That year, when I was serving in the clinic, I heard a clan member screaming in pain from the hospital bed. I asked him if he didn’t take painkillers? He said to me: ‘The medical staff think that the aborigines love to drink, and painkillers are useless’. “

This is what Yimao saw at the medical scene when he was a nurse. And this isn’t the first time she’s heard such a thing.

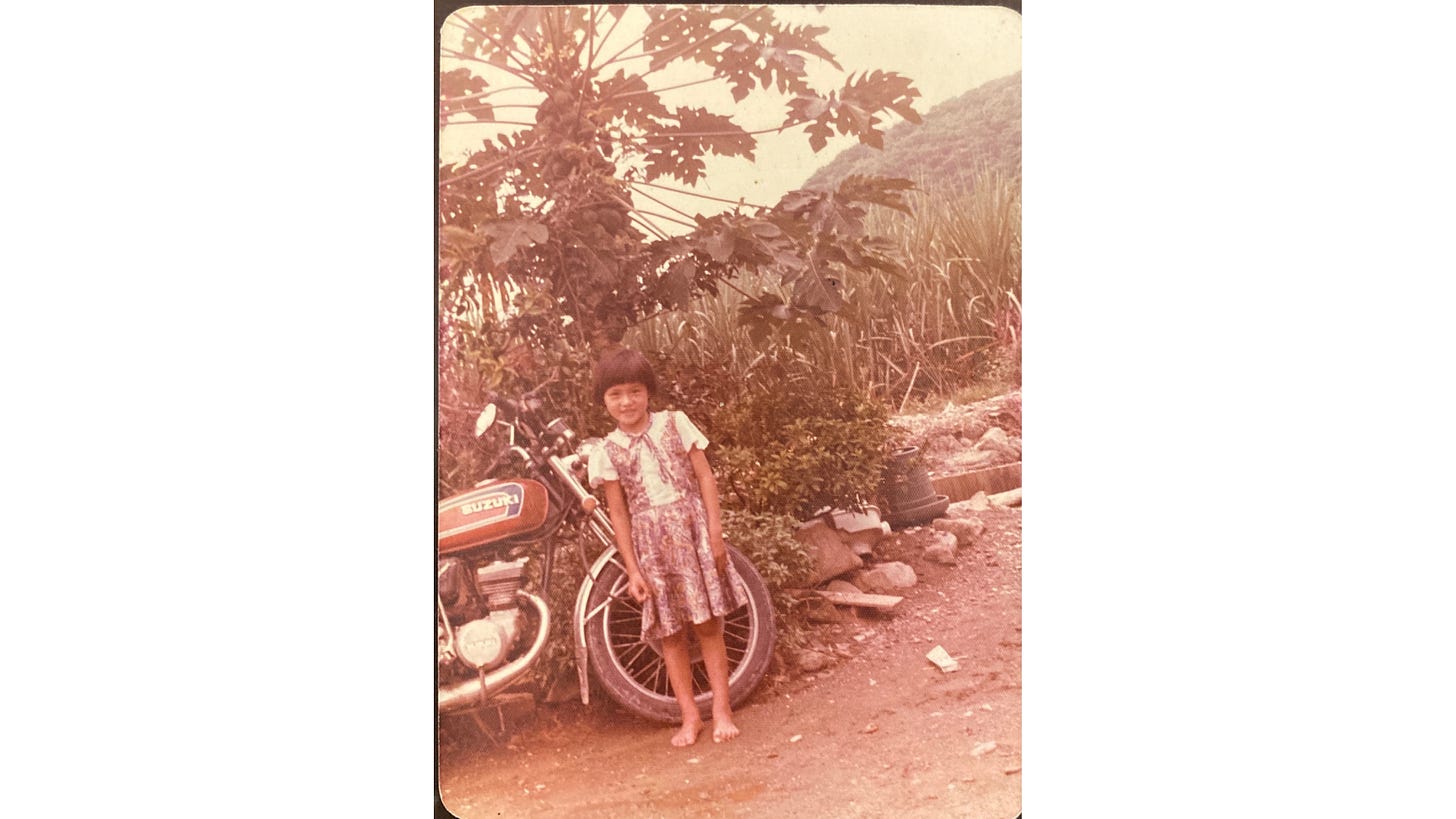

Yimao’s father is Han Chinese and his mother is Taroko. Since childhood, their family lived in Guofuli, Hualien County, where the Sakilaya and Han people live together.

“You are a fanboy, your mother is a fangirl, don’t come here.”

She remembers that when she was a child playing with the neighbor’s children, she often saw disgust in the eyes of adults, and some even drove her away directly and told her not to interact with her own children. She also remembered that her mother would teach her to speak the ethnic language when she was a child, but in the unfriendly neighborhood atmosphere, her mother gradually stopped teaching her and even started to speak Taiwanese. In addition, the school also banned the speaking of the ethnic language at the time, and if you did, you would be fined.

“When I was young, I was very unconvinced by the voices of discrimination. Because I didn’t want to lose, I felt that I had to work harder.”

In order not to let the neighbors look down on her, Yimao studied hard, and her grades were getting better and better. She also began to take an interest in medicine when she was in middle school. At that time, both of her parents had problems with their physical health. During the process of accompanying her family to the hospital, she felt the greatness of nursing work, and decided to enter a nursing college. After graduation, she entered the hospital as a nurse.

At that time, she thought that it would be a good choice if she could use this as a career, but she did not expect that it would become a “vocation”.

The World Walk has important stories you haven’t read yet. We focus on global issues from a gender perspective, complementing stories of dilemma, breakthrough, connection, and change that traditional power perspectives ignore.

Please pay a subscription to become our partner and walk with women around the world.

The medical system is “ethnic blind” and cannot cure injuries

“In the hospital, whenever we saw the faces of our tribesmen, we probably knew that each other was aboriginal. They would ask me: ‘Where are you from?’ communicate with each other.”

But in those few years, Yimao often saw the clansmen being treated unkindly.

“There are often medical staff who will say to the returning case: ‘Why are you back? Have you been drinking again?’ or insinuating that his profession is an alcoholic? A lot of stigma is permeated in the interaction.”

She also observed that when medical staff explained their illnesses or health education knowledge to the tribesmen, most of them didn’t stay for long.

Due to the gap in knowledge and education between the clansmen and medical staff, the clansmen often do not know how to reflect their needs or take the initiative to ask their own medical conditions, and many doctors feel that they cannot understand too many explanations, causing many aboriginal patients to return home. I don’t know how to take care of myself.

For example, some patients with hip replacements need complete health education information, including: What are the contraindications to movements after returning home? How to wash up? How soon can I start work and use transportation? How to avoid joint slippage? When will you return to the hospital?

Without a complete understanding of this aspect, many aboriginal men will act heroically, thinking that they can start work as long as there is no pain. As a result, the artificial joint often slips, and they have to return to the hospital, and the day they can return to the workplace is far away. In addition, the traditional aboriginal society has no concept of saving and financial management, and most of the men are the economic backbone of the family. Once they are unable to work, the livelihood of many families will collapse instantly.

In the hospital, only a very small number of people can afford to live in a single room when they are hospitalized. Most people generally choose free beds paid by health insurance, and five or six people live in one room.

The colonial history of the past hundreds of years has made indigenous peoples relatively disadvantaged in terms of socioeconomic status, educational level or language and culture. Over the years, in the “Top Ten Causes of Death in China” list, the proportion of aboriginal people suffering from cancer, hepatitis, diabetes, heart disease, etc. is higher than that of other ethnic groups.

There are many reasons behind this: for example, the indigenous ethnic groups that are socially, economically and educationally disadvantaged have a relatively large working class and relatively insufficient health awareness. In most cases of high-risk, high-intensity labor work, overwork injuries and occupational accidents are more likely to occur; if health policies are not culturally appropriate, they will be intertwined, resulting in a high rate of illness among indigenous peoples.

Yimao sighed that if the medical system fails to realize that the health of the aboriginal people is also affected by social factors such as economy, education, gender, etc., and continues to lack awareness of the culture and care of the aboriginal people, it will shorten the average life expectancy gap between the original and Han people. .

She also said that she had seen too many cases in the hospital, but there was limited change she could make. Twenty years ago, the rank of the nurse was not high: in the clinic, the nurse had to clean the environment; in the medical center, in the face of the doctor’s order, the nurse had no qualifications to question, and their doctor’s order, like a decree, was the final decision.

Seeing the loopholes in the medical system, she realized that only through education and systematically cultivating professional workers with sufficient cultural sensitivity can the problems encountered by indigenous peoples in the medical and health care system be solved.

Awareness of “cultural care” needed from education to policy

In 2013, the Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Council held the “Aboriginal National Affairs Conference” for the first time. In this meeting, Yimao first proposed to incorporate the concept of “cultural care” into the policy.

Cultural care means that professional caregivers must have the ability to understand the culture of different ethnic backgrounds, such as diet, social and economic conditions, language, customs, etc., and under the context of this knowledge and ability, “tailor-made” the most appropriate care.

“In mainstream education, the concept of ‘cultural care’ is rarely incorporated, resulting in a lack of awareness in many policies. With this concept, we can provide different knowledge, attitudes and behaviors of care according to different ethnic groups.”

“For example, the way to prevent gout with the alpine indigenous group is not to tell him not to eat seafood, because it is not his staple food, but to talk to him about the internal organs of animals not to eat (such as the precious flying squirrels caught in the hunting season) Or the internal organs of wild boars, etc.), heavy salt… These are the most important connotations of cultural care.”

In addition to education, Yimao believes that only by implementing policies can changes be made at the source.

“The hospital’s executive level lacks specific measures for cultural care. On the one hand, people’s awareness is not high. Before forcing medical personnel to change their licenses, they need to receive continuing education on this topic; , but the curriculum planning did not force the inclusion of indigenous health and cultural care as the major subjects, which is like selling dog meat.”

In 2014, under the suggestion of Yimao, the Aboriginal will change the name of “Day Care Station for the Elderly of Aboriginal Tribes” to “Cultural Health Station”. Since 2015, she has personally traveled to more than 80 tribes in Taiwan, undertook the education and training of 109 cultural and health stations, and cultivated the cultural care ability of hometown care attendants.

In the past, the main functions of the care station were to deliver meals to the elderly and to ask for greetings by phone. After changing its name to the cultural health station, she encouraged localities to integrate traditional food, skills, language, clothing and other cultural elements into the care model.

Yimao gave an example. In terms of diet, she encourages all regions to incorporate traditional wild vegetables and local ingredients into their meals to supplement nutrition for the elderly. In terms of curriculum design, she changed the use of foreign textbooks or dances in the past. She allowed each ethnic group to return to its own culture, such as designing a set of movements with traditional ballads, or asking the elderly to draw traditional family houses and tribal maps on paper from memory. As a mental exercise to delay disability. Even the cultural health station guides the elders to use traditional wisdom and use tribal agricultural products to make essential oils.

Today, the “Cultural Health Station” has been established for ten years. It has long been not just a site for promoting health education, but also silently promoting the revival of traditional culture. In the evaluation report for the cultural health station, the indigenous people will find that the elderly who participate in the health station have a relatively high sense of happiness.

In the past six years, Yimao has also continued to engage in academic research on aboriginal health, and served as the project host of the Aboriginal Association’s “Human Research Project Consultation to Obtain Aboriginal Consent and Agreement on Commercial Interests and Application Methods”.

In the process of dialogue with different academic teams and indigenous communities, she found that many academic teams are unaware of the research process and results, which may bring cultural risks and threats to ethnic groups. For example, some remarks alleging that Aboriginal people cannot pay health insurance premiums, Aboriginal women have open sexual attitudes, etc. These unsubstantiated stereotypes and prejudices are often influenced by academic articles from many years ago.

With the increasing awareness of human research ethics and the gradual improvement of relevant legislation, the establishment and use of these databases in the future must be carried out under the conditions of openness and transparency and inclusion of the right of indigenous peoples to self-determination.

resistance and persistence

As a Taroko woman, self-realization is not an easy task.

When she was a child, some relatives of the Atayal even asked her: “Why are you Taroko women so obedient? They would not leave even if they were raped, if we Atayal would have run away long ago.”

Yimao has been expected to be a submissive, hard-working, overall-minded character since childhood. Her parents believe that when girls grow up, they want to get married and have children, so they don’t have to study too high. Therefore, in the process of academic pursuit, she not only had to face the doubts of her father, but also encountered the contradiction of taking into account her family and personal ideals.

But contrary to her parents’ expectations, she pursued self-realization along the academic road and promoted the improvement of medical care rights for Taiwan’s aborigines. It was only because she had worked in a hospital that she saw all the discrimination faced by the tribe and felt the mission she had on her shoulders.

Yimao said that when she was in college, she was exposed to the history of Taiwan and saw the various pasts of the aborigines who were plundered in the colonial history, and she developed a sense of ethnicity in her heart; and her work experience in the hospital made her feel strongly that the medical care system has an impact on the aborigines. The lack of cultural awareness has become the driving force behind her continuous advancement in medicine.

“As long as the other half has enough understanding and support, it is absolutely possible for an aboriginal woman to balance family and self-realization,” she said. “The gentle and firm characteristics of women have given me different advantages in policy communication over the years. ”

In the past two decades, Yimao has continuously triggered reforms on the way to promote the health of indigenous peoples. “I also feel that there are a lot of things to do, and I also want to travel around the world to see what experience I can bring back to Taiwan, and I have a lot of expectations for my life.”

“I also hope that indigenous women can be brave enough to pursue the things they love, because it is more difficult for us to escape the framework than the Han people, but we must be persistent enough, because there is no such thing as To live a smooth life, take setbacks for granted, and always have the courage to face them.” (End)

About the Author| Xiao Zihan (Contributing Writer)

Subscribe to the Walk Around Newsletter and we’ll deliver:

[Members only] Go original: a good story that others have not written yet

An Evening News Every Day: A selection of daily news summaries for you

Weekly Newsletter: Good articles from around the world that you may have missed

A Weekly Note: A Weekly Guide to Online Activities

【Exclusive benefits for other members】» See here

This article is reprinted from: https://sehseh.substack.com/p/65e

This site is for inclusion only, and the copyright belongs to the original author.